Lower respiratory tract infections include infectious processes of the lungs and bronchi, pneumonia, bronchitis, bronchiolitis, and lung abscess.

Bronchitis

Acute bronchitis

- Bronchitis refers to an inflammatory condition of the large elements of the tracheobronchial tree that is usually associated with a generalized respiratory infection. The inflammatory process does not extend to include the alveoli. The disease entity is frequently classified as either acute or chronic.

- Acute bronchitis most commonly occurs during the winter months. Cold, damp climates and/or the presence of high concentrations of irritating substances such as air pollution or cigarette smoke may precipitate attacks.

Pathophysiology

- Respiratory viruses are by far the most common infectious agents associated with acute bronchitis. The common cold viruses, rhinovirus and coronavirus, and lower respiratory tract pathogens, including influenza virus, adenovirus, and respiratory syncytial virus, account for the majority of cases. Mycoplasma pneumoniae also appears to be a frequent cause of acute bronchitis. Other bacterial causes include Chlamydia pneumoniae and Bordetella pertussis.

- Infection of the trachea and bronchi causes hyperemic and edematous mucous membranes and an increase in bronchial secretions. Destruction of respiratory epithelium can range from mild to extensive and may affect bronchial mucociliary function. In addition, the increase in bronchial secretions, which can become thick and tenacious, further impairs mucociliary activity. Recurrent acute respiratory infections may be associated with increased airway hyperreactivity and possibly the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive lung disease.

Clinical Presentation

- Bronchitis is primarily a self-limiting illness and rarely a cause of death. Acute bronchitis usually begins as an upper respiratory infection. The patient typically has nonspecific complaints such as malaise and headache, coryza, and sore throat.

- Cough is the hallmark of acute bronchitis. It occurs early and will persist despite the resolution of nasal or nasopharyngeal complaints. Frequently, the cough is initially nonproductive but progresses, yielding mucopurulent sputum.

- Chest examination may reveal rhonchi and coarse, moist rales bilaterally. Chest radiographs, when performed, are usually normal.

- Bacterial cultures of expectorated sputum are generally of limited utility because of the inability to avoid normal nasopharyngeal flora by the sampling technique. Viral antigen detection tests can be used when a specific diagnosis is necessary. Cultures or serologic diagnosis of M. pneumoniae and culture or direct fluorescent antibody detection for B. pertussis should be obtained in prolonged or severe cases when epidemiologic considerations would suggest their involvement.

Desired Outcome

The goals of therapy are to provide comfort to the patient and, in the unusually severe case, to treat associated dehydration and respiratory compromise.

Treatment

- The treatment of acute bronchitis is symptomatic and supportive in nature. Reassurance and antipyretics alone are often sufficient. Bedrest and mild analgesic-antipyretic therapy are often helpful in relieving the associated lethargy, malaise, and fever. Aspirin or acetaminophen (650 mg in adults or 10-15 mg/kg per dose in children with a maximum daily adult dose of 4 g and 60 mg/kg for children) or ibuprofen (200 to 800 mg in adults or 10 mg/kg per dose in children with a maximum daily dose of 3.2 g for adults and 40 mg/kg for children) is administered every 4 to 6 hours.

- Patients should be encouraged to drink fluids to prevent dehydration and possibly decrease the viscosity of respiratory secretions.

- In children, aspirin should be avoided and acetaminophen used as the preferred agent because of the possible association between aspirin use and the development of Reye’s syndrome.

- Mist therapy and/or the use of a vaporizer may further promote the thinning and loosening of respiratory secretions.

- Persistent, mild cough, which may be bothersome, may be treated with dextromethorphan; more severe coughs may require intermittent codeine or other similar agents.

- Routine use of antibiotics in the treatment of acute bronchitis is discouraged; however, in patients who exhibit persistent fever or respiratory symptomatology for more than 4 to 6 days, the possibility of a concurrent bacterial infection should be suspected.

- When possible, antibiotic therapy is directed toward anticipated respiratory pathogen(s) (i.e., Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae) and/or those demonstrating a predominant growth upon throat culture.

- M. pneumoniae, if suspected by history or positive cold agglutinins (titers greater than or equal to 1:32) or if confirmed by culture or serology, may be treated with erythromycin or its analogs (e.g., clarithromycin or azithromycin). Also, a fluoroquinolone with activity against these pathogens (gatifloxacin or increased dose levofloxacin) may be used in adults.

- During known epidemics involving the influenza A virus, amantadine or rimantadine may be effective in minimizing associated symptomatology if administered early in the course of the disease.

Chronic bronchitis

Chronic bronchitis is a nonspecific disease that primarily affects adults.

Pathophysiology

- Chronic bronchitis is a result of several contributing factors, including cigarette smoking; exposure to occupational dusts, fumes, and environmental pollution; and bacterial (and possibly viral) infection.

- In chronic bronchitis, the bronchial wall is thickened and the number of mucus-secreting goblet cells in the surface epithelium of both larger and smaller bronchi is markedly increased. Hypertrophy of the mucus glands and dilatation of the mucus gland ducts are also observed. As a result of these changes, patients with chronic bronchitis have substantially more mucus in their peripheral airways, further impairing normal lung defenses and causing mucus plugging of the smaller airways.

Continued progression of this pathology can result in residual scarring of small bronchi, augmenting airway obstruction and the weakening of bronchial walls.

Clinical Presentation

- The hallmark of chronic bronchitis is cough that may range from a mild «smoker’s» cough to severe incessant coughing productive of purulent sputum. Expectoration of the largest quantity of sputum usually occurs upon arising in the morning, although many patients expectorate sputum throughout the day. The expectorated sputum is usually tenacious and can vary in color from white to yellow-green.

- By definition, any patient who reports coughing up sputum on most days for at least three consecutive months each year for two consecutive years suffers from chronic bronchitis. TABLE Classification System for Patients with Chronic Bronchitis and Initial Treatment Options presents a classification and treatment scheme for chronic bronchitis.

| TABLE. Classification System for Patients with Chronic Bronchitis and Initial Treatment Options |

| Baseline Status |

Criteria or Risky Factors |

Usual Pathogens |

Initial Treatment Options |

| Class I |

| Acute tracheobronchitis |

No underlying structural disease |

Usually a virus |

1. None unless symptoms persist 2. Amoxicillin; amoxicillin-clavulanate; or a macrolide/azalide |

| Class II |

| Chronic bronchitis |

FEV1 >50% predicted value, increased sputum volume and purulence |

Hemophilus influenzae, Hemophilus spp., Moraxella catarrhalis, Streptococcus pneumoniae (β- lactam resistance possible) |

1. Amoxicillin, or fluoroquinolone if prevalence of H. influenzae resistance to amoxicillin is >20% 2. Fluoroquinolone, amoxicillin-clavulanate, azithromycin, tetracycline, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole |

| Class III |

| Chronic bronchitis with complications |

FEV1 < 50% predicted value, increased sputum volume and purulence, advanced age, at least four flares per year, or significant comorbidity |

Same as class II; also Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, and other gram-negative organisms (β- lactam resistance common) |

1. Fluoroquinolone 2. Expanded spectrum cephalosporin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, or azithromycin |

| Class intravenous |

| Chronic bronchial Infection |

Same as for class III plus yearlong production of purulent sputum |

Same as class III |

1. Oral or parenteral fluoroquinolone, carbapenem or expanded spectrum cephalosporin |

| 1, Preferred therapy; 2, alternative treatment options. Fluoroquinolone: ciprofloxacin, gatifloxacin, levofloxacin; tetracycline: tetracycline HCL, doxycycline; carbapenem: imipenem-cilastatin, meropenem; expanded-spectrum cephalosporin: ceftazidime, cefepime. |

|

| TABLE. Clinical Presentation of Chronic Bronchitis |

| Signs and Symptoms |

| Cyanosis (advanced disease) Obesity |

| Physical Examination |

| Chest auscultation usually reveals inspiratory and expiratory rales, rhonchi, and mild wheezing with an expiratory phase that is frequently prolonged. There is hyperresonance on percussion with obliteration of the area of cardiac dullness Normal vesicular breathing sounds are diminished Clubbing of digits (advanced disease) |

| Chest Radiograph |

| Increase in the anteroposterior diameter of the thoracic cage (observed as a barrel chest) Depressed diaphragm with limited mobility |

| Laboratory Tests |

| Erythrocytosis (advanced disease) |

| Pulmonary Function Tests |

| Decreased vital capacity Prolonged expiratory flow |

|

- With the exception of pulmonary findings, the physical examination of patients with mild to moderate chronic bronchitis is usually unremarkable (Table Clinical Presentation of Chronic Bronchitis).

- An increased number of polymorphonuclear granulocytes in sputum often suggests continual bronchial irritation, whereas an increased number of eosinophils may suggest an allergic component. The most common bacterial isolates (expressed in percentages of total cultures) identified from sputum culture in patients experiencing an acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis are as follows:

| Haemophilus influenzae |

24% to 26% (often β- lactamase +) |

| Haemophilus parainfluenzae |

20% |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae |

15% |

| Moraxella catarrhalis |

15% (often β- lactamase +) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae |

4% |

| Serratia marcescens |

2% |

| Neisseria meningitidis |

2% (often β- lactamase +) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

2% |

|

Desired Outcome

The goals of therapy for chronic bronchitis are to reduce the severity of symptoms, to ameliorate acute exacerbations, and to achieve prolonged infection-free intervals.

Treatment

General Principles

- A complete occupational/environmental history for the determination of exposure to noxious, irritating gases, as well as cigarette smoking, must be assessed. Attempts must be made to reduce exposure to bronchial irritants.

- Humidification of inspired air may promote the hydration (liquefaction) of tenacious secretions, allowing for more effective sputum production. The use of mucolytic aerosols (e.g., N-acetylcysteine; deoxyribonuclease [DNase]) is of questionable therapeutic value.

- Postural drainage may assist in promoting clearance of pulmonary secretions.

Pharmacologic Therapy

- Oral or aerosolized bronchodilators (e.g., albuterol aerosol) may be of benefit to some patients during acute pulmonary exacerbations. For patients who consistently demonstrate limitations in airflow, a therapeutic change of bronchodilators should be considered.

- The use of antimicrobials has been controversial, although antibiotics are an important component of treatment. Agents should be selected that are effective against likely pathogens, have the lowest risk of drug interactions, and can be administered in a manner that promotes compliance (see Table Classification System for Patients with Chronic Bronchitis and Initial Treatment Options).

- Selection of antibiotics should consider that up to 30% to 40% of H. influenzae and 95% of M. pneumoniae are β- lactamase producers, and up to 30% of S. pneumoniae are at least moderately penicillin resistant.

- Antibiotics commonly used in the treatment of these patients and their respective adult starting doses are outlined in TABLE Oral Antibiotics Commonly Used for the Treatment of Acute Respiratory Exacerbations in Chronic Bronchitis. Duration of symptom-free periods may be enhanced by antibiotic regimens using the upper limit of the recommended daily dose for 10 to 14 days.

- Ampicillin is often considered the drug of choice for the treatment of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis. Unfortunately, the need for multiple repeat daily doses (4 times daily) and the increasing incidence of penicillin-resistant β- lactamase-producing strains of bacteria have limited the usefulness of this safe and cost-effective antibiotic.

- The value of macrolides when Mycoplasma is involved is unquestioned. Azithromycin should be considered as the macrolide of choice for Mycoplasma.

| TABLE. Oral Antibiotics Commonly Used for the Treatment of Acute Respiratory Exacerbations in Chronic Bronchitis |

| Antibiotic |

Usual Adult Dose(g) |

Dose Schedule (doses/day) |

| Preferred Drugs |

| Ampicillin |

0.25-0.5 |

4 |

| Amoxicillin |

0.5 |

3 |

| Cefprozil |

0.5 |

2 |

| Cefuroxime |

0.5 |

2 |

| Ciprofloxacin |

0.5-0.75 |

2 |

| Gatifloxacin |

0.4 |

1 |

| Levofloxacin |

0.5-0.75 |

1 |

| Doxycycline |

0.1 |

2 |

| Minocycline |

0.1 |

2 |

| Tetracycline HCl |

0.5 |

4 |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate |

0.5 |

3 |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole |

1 DSa |

2 |

| Supplemental Drugs |

| Azithromycin |

0.25-0.5 |

1 |

| Erythromycin |

0.5 |

4 |

| Clarithromycin |

0.25-0.5 |

2 |

| Cefixime |

0.4 |

1 |

| Cephalexin |

0.5 |

4 |

| Cefaclor |

0.25-0.5 |

3 |

| aDS, double-strength tablet (160 mg trimethoprim/800 mg sulfamethoxazole). |

|

- The fluoroquinolones are effective alternative agents for adults, particularly when gram-negative pathogens are involved, or for more severely ill patients. Many S. pneumoniae are resistant to older fluoroquinolones such as ciprofloxacin, necessitating the use of newer agents such as gatifloxacin.

- In patients whose history suggests recurrent exacerbations of their disease that might be attributable to certain specific events (i.e., seasonal, winter months), a trial of prophylactic antibiotics might be beneficial. If no clinical improvement is noted over an appropriate period (e.g., 2 to 3 months per year for 2 to 3 years), prophylactic therapy could be discontinued.

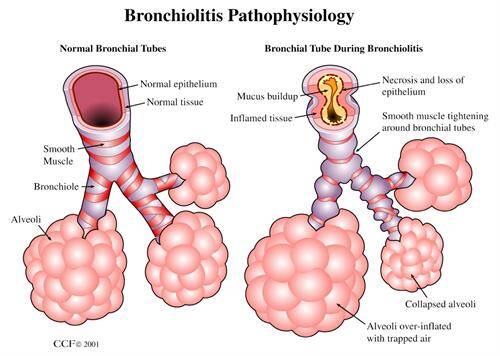

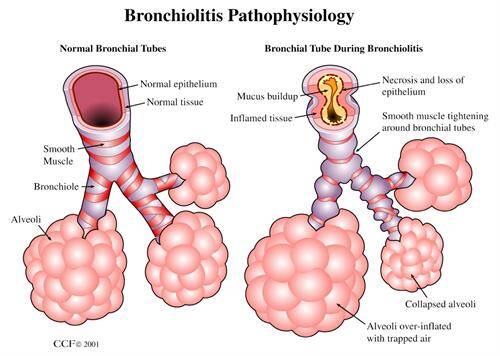

Bronchiolitis

- Bronchiolitis is an acute viral infection of the lower respiratory tract of infants that shows a definite seasonal pattern (peaks during the winter months and persists through early spring). The disease most commonly affects infants between the ages of 2 and 10 months.

- Respiratory syncytial virus is the most common cause of bronchiolitis, accounting for 45% to 60% of all cases. Parainfluenza viruses are the second most common cause. Bacteria serve as secondary pathogens in only a small minority of cases.

Clinical Presentation

- The most common clinical signs of bronchiolitis are found in TABLE Clinical Presentation of Bronchiolitis.

- As a result of limited oral intake due to coughing combined with fever, vomiting, and diarrhea, infants are frequently dehydrated.

- The diagnosis of bronchiolitis is based primarily on history and clinical findings. The isolation of a viral pathogen in the respiratory secretions of a wheezing child establishes a presumptive diagnosis of infectious bronchioloitis.

Treatment

- Bronchiolitis is a self-limiting illness and usually requires no therapy (other than reassurance and antipyretics) unless the infant is hypoxic or dehydrated.

- In severely affected children, the mainstays of therapy for bronchiolitis are oxygen therapy and intravenous fluids.

- Aerosolized β- adrenergic therapy appears to offer little benefit for the majority of patients but may be useful in the child with a predisposition toward bronchospasm.

| TABLE. Clinical Presentation of Bronchiolitis |

| Signs and Symptoms |

| Prodrome with irritability, restlessness, and mild fever Cough and coryza Vomiting, diarrhea, noisy breathing, and an increase in respiratory rate as symptoms progress Labored breathing with retractions of the chest wall, nasal flaring, and grunting |

| Physical Examination |

| Tachycardia and respiratory rate of 40-80/min in hospitalized infants Wheezing and inspiratory rales Mild conjunctivitis in one third of patients Otitis media in 5-10% of patients |

| Laboratory Examinations |

| Peripheral white blood cell count normal or slightly elevated Abnormal arterial blood gases (hypoxemia and, rarely, hypercarbia) |

|

- Because bacteria do not represent primary pathogens in the etiology of bronchiolitis, antibiotics should not be routinely administered. However, many clinicians frequently administer antibiotics initially while awaiting culture results because the clinical and radiographic findings in bronchiolitis are often suggestive of a possible bacterial pneumonia.

- Ribavirin may be considered for bronchiolitis caused by respiratory syncytial virus in a subset of patients (those with underlying pulmonary or cardiac disease or with severe acute infection). Use of the drug requires special equipment (small-particle aerosol generator) and specifically trained personnel for administration via oxygen hood or mist tent.

Evaluation of therapeutic outcomes

- With community-acquired pneumonia, time for resolution of cough, sputum production, and presence of constitutional symptoms (e.g., malaise, nausea or vomiting, lethargy) should be assessed. Progress should be noted in the first 2 days, with complete resolution in 5 to 7 days.

| TABLE. Empirical Antimicrobial Therapy for Pneumonia in Pediatric Patientsa |

|

| Age |

Usual Pathogen(s) |

Presumptive Therapy |

| 1 month |

Group B streptococcus, Hemophilus influenzae (nontypable), Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria, cytomegalovirus, RSV, adenovirus |

Ampicillin-sulbactam, cephalosporinb carbapenemc |

| |

Ribavirin for RSV |

| 1-3 months |

Chlamydia, possibly Ureaplasma, cytomegalovirus, Pneumocystis carinii (afebrile pneumonia syndrome) |

Macrolide-azalide,d trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole |

| RSV |

Ribavirin |

| Pneumococcus, S. aureus |

Semisynthetic penicilline or cephalosporinf |

| 3 months-6 yr |

Pneumococcus, H. influenzae, RSV, adenovirus, Parainfluenza |

Amoxicillin or cephalosporinf Ampicillin-sulbactam, amoxicillin-clavulanate Ribavirin for RSV |

| >6 yr |

Pneumococcus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, adenovirus |

Macrolide/azalided cephalosporin,f amoxicillin-clavulanate |

| cytomegalovirus, cytomegalovirus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus. |

| aSee section on treatment of bacterial pneumonia. bThird-generation cephalosporin: ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, cefepime. Note that cephalosporins are not active against Listeria. cCarbapenem: imipenem-cilastatin, meropenem. dMacrolide/azalide: erythromycin, clarithromycin-azithromycin. eSemisynthetic penicillin: nafcillin, oxacillin. fSecond-generation cephalosporin: cefuroxime, cefprozil. See text for details regarding ribavirin treatment for RSV infection. |

|

| TABLE. Antibiotic Doses for the Treatment of Bacterial Pneumonia |

| |

|

Daily Antibiotic dose |

| Antibiotic Class |

Antibiotic |

Pediatric (mg/kg/day) |

Adult (total dose/day) |

| Macrolide |

Clarithromycin |

15 |

0.5-1 g |

| Erythromycin |

30-50 |

1-2 g |

| Azalide |

Azithromycin |

10 mg/kg x 1 day, then 5 mg/kg/day x 4 days |

500 mg day 1, then 250 mg/day x 4 days |

| Tetracyclinea |

Tetracycline HCL |

25-50 |

1-2 g |

| Oxytetracycline |

15-25 |

0.25-0.3 g |

| Penicillin |

Ampicillin |

100-200 |

2-6 g |

| Amoxicillin/amoxicillin-clavulanateb |

40-90 |

0.75-1 g |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam |

200-300 |

12 g |

| Ampicillin-sulbactam |

100-200 |

4-8 g |

| Extended-spectrum cephalosporins |

Ceftriaxone |

50-75 |

1-2 g |

| |

Ceftazidime |

150 |

2-6 g |

| Cefepime |

100-150 |

2-4 g |

| Fluoroquinolones |

Gatifloxacinc |

10-20 |

0.4 g |

| |

Levofloxacin |

10-15 |

0.5-0.75 g |

| Ciprofloxacin |

20-30 |

0.5-1.5 g |

| Aminoglycosides |

Gentamicin |

7.5 |

3-6 mg/kg |

| Tobramycin |

7.5 |

3-6 mg/kg |

| Note: Doses may be increased for more severe disease and may require modification in patients with organ dysfunction. aTetracyclines are rarely used in pediatric patients, particularly in those younger than 8 yr of age because of tetracycline-induced permanent tooth discoloration. bHigher dose amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate (e.g., 90 mg/kg/day) is used for penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae. cFluoroquinolones are avoided in pediatric patients because of the potential for cartilage damage; however, their use in pediatrics is emerging. Doses shown are extrapolated from adults and will require further study. |

|

TABLE. Guidelines for the Empirical Treatment of Community-Acquired Pneumonia

| |

| Clinical Setting |

Empirical Therapy |

| Outpatients |

Macrolide/azalide, doxycycline, or fluoroquinolone |

| Inpatients, general medical ward |

Extended-spectrum cephalosporin + macrolide/azalide or β- lactam/β- lactamase inhibitor + macrolide/azalide or fluoroquinolone |

| Inpatients, intensive care unit |

Extended-spectrum cephalosporin or β- lactam/β- lactamase inhibitor + fluoroquinolone or macrolide/azalide |

|

- With nosocomial pneumonia, the above parameters should be assessed along with white blood cell counts, chest radiograph, and blood gas determinations.