Since most occupational exposures to HIV do not result in transmission of the virus, the potential toxicity of PEP regimens must be considered carefully and, whenever possible, prophylaxis should be implemented in consultation with clinicians who have expertise in antiretroviral therapy and HIV transmission. Modification of the recommended regimens may be appropriate based on factors such as whether the source patient is known or suspected of being infected with drug-resistant strains of HIV; the local availability of antiretroviral agents; and the medical condition, concurrent drug therapy, and drug toxicity in the exposed health-care worker.

The CDC has made the following recommendations for PEP following occupational exposure to HIV:

- The recommended basic 2-drug PEP regimen is oral zidovudine (600 mg daily in 2 or 3 divided doses) and oral lamivudine (150 mg twice daily). Alternatively, a basic 2-drug regimen of oral lamivudine (150 mg twice daily) and oral stavudine (40 mg twice daily; 30 mg twice daily in those weighing less than 60 kg) or oral didanosine (400 mg daily; 125 mg twice daily in those weighing less than 60 kg) and oral stavudine (40 mg twice daily; 30 mg twice daily in those weighing less than 60 kg) can be used.

- The expanded 3-drug PEP regimen includes the basic 2-drug regimen and either oral indinavir (800 mg every 8 hours), oral nelfinavir (750 mg 3 times daily or 1250 mg twice daily), efavirenz (600 mg once daily), or oral abacavir (300 mg twice daily).

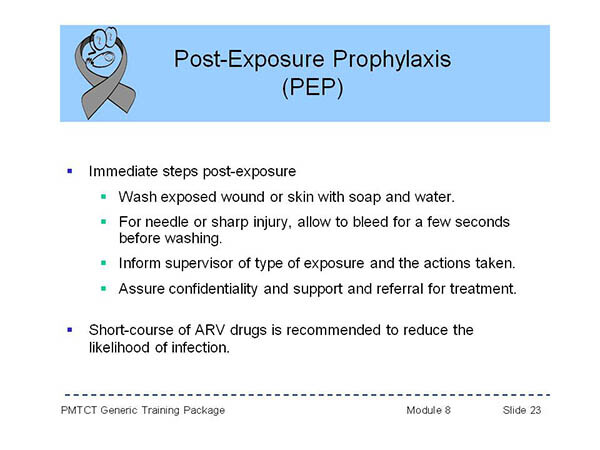

- If PEP is appropriate for the exposure and the exposed health-care worker elects to receive such therapy, it should be initiated as soon as possible following exposure. To ensure timely access to PEP, an occupational exposure should be regarded as an urgent medical concern. When there are some concerns regarding the most appropriate drugs to administer, it probably is preferable to immediately initiate therapy with the basic PEP regimen rather than delaying PEP.

- The optimal duration of PEP is unknown, but PEP probably should be administered for 4 weeks, if tolerated.

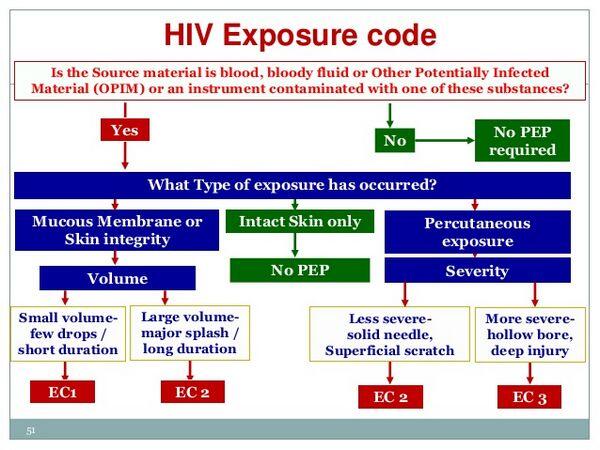

- If the type of exposure involved mucous membrane or nonintact skin (e.g., exposed skin is chapped, abraded, or afflicted with dermatitis) but only involved a small volume of blood or other infectious material (e.g., a few drops), PEP is not be warranted if the source is HIV negative. If the source is HIV positive and asymptomatic or has a low viral load (plasma HIV-1 RNA less than 1500 copies/ml), use of the basic 2-drug regimen can be considered. If the source is HIV positive and is symptomatic, has AIDS, acute seroconversion, or a high viral load, use of the basic 2-drug regimen is recommended. If the source is of unknown HIV status (e.g., deceased with no samples available for testing), PEP generally is not warranted but use of the basic 2-drug regimen can be considered if the source had HIV risk factors. If the source is unknown (e.g., a needle from a sharps disposal container), PEP generally is not warranted but the basic 2-drug regimen may be considered in settings where exposure to HIV-infected individuals is likely.

- If the type of exposure involved mucous membrane or nonintact skin and involved a large volume of blood or other infectious material (e.g., major blood splash), PEP is not warranted if the source is HIV-negative. If the source is HIV positive and asymptomatic or has a low viral load (plasma HIV-1 RNA less than 1500 copies/ml), use of the basic 2-drug regimen is recommended. If the source is HIV positive and is symptomatic, has AIDS, acute seroconversion, or a high viral load, use of the expanded 3-drug regimen is recommended. If the source is of unknown HIV status (e.g., deceased with no samples available for testing), PEP generally is not warranted but use of the basic 2-drug regimen can be considered if the source had HIV risk factors. If the source is unknown (e.g., a needle from a sharps disposal container), PEP generally is not warranted but the basic 2-drug regimen may be considered in settings where exposure to HIV-infected individuals is likely.

- If the type of exposure involved a percutaneous injury considered to be less severe (e.g., solid needle and superficial injury), PEP is not warranted if the source is HIV negative. If the source is HIV positive and asymptomatic or has a low viral load (plasma HIV-1 RNA less than 1500 copies/ml), use of the basic 2-drug regimen is recommended. If the source is HIV positive and is symptomatic, has AIDS, acute seroconversion, or a high viral load, use of the expanded 3-drug regimen is recommended. If the source is of unknown HIV status (e.g., deceased with no samples available for testing), PEP generally is not warranted but use of the basic 2-drug regimen can be considered if the source had HIV risk factors. If the source is unknown (e.g., splash from inappropriately disposed blood), PEP generally is not warranted but the basic 2-drug regimen may be considered in settings where exposure to HIV-infected individuals is likely.

- If the type of exposure involved a percutaneous injury considered to be more severe (e.g., large-bore hollow needle, deep puncture, visible blood on device, or needle used in patient’s artery or vein), PEP is not warranted if the source is HIV negative. If the source is HIV positive and asymptomatic or has a low viral load (plasma HIV-1 RNA less than 1500 copies/ml), use of the expanded 3-drug regimen is recommended. If the source is HIV positive and is symptomatic, has AIDS, acute seroconversion, or a high viral load, use of the expanded 3-drug regimen is recommended. If the source is of unknown HIV status (e.g., deceased with no samples available for testing), PEP generally is not warranted but use of the basic 2-drug regimen can be considered if the source had HIV risk factors. If the source is unknown (e.g., splash from inappropriately disposed blood), PEP generally is not warranted but the basic 2-drug regimen may be considered in settings where exposure to HIV-infected individuals is likely.

- Health-care workers with occupational exposure to HIV should receive follow-up counseling and medical evaluation, including HIV antibody tests at baseline and periodically for at least 6 months after the exposure (e.g., at 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 6 months), and should be advised to observe precautions to prevent possible secondary transmission. Health-care workers who become infected with HIV should receive appropriate medical care.

- Clinicians seeking information and guidance regarding the management of an occupational exposure to HIV and additional information on PEP can consult the National Clinicians’ Postexposure Prophylaxis Hotline (PEPline) at 888-448-4911 or http://www.ucsf.edu/hivcntr or the Needlestick! website at http://needlestickmednet.ucla.edu. Any unusual or severe toxicity associated with PEP should be reported to the manufacturer and/or the FDA MedWatch program at 800-332-1088 or http://www.fda.gov/medwatch. In addition, cases of occupationally-acquired HIV or failures of PEP should be reported to the CDC at 800-893-0485

- Antiretrovirals for Postexposure Prophylaxis following Sexual Assault or Nonoccupational Exposures to HIV

Antiretroviral agents have been used in a limited number of individuals for HIV postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) following sexual exposures (e.g., sexual assault, inadvertent artificial insemination from an HIV-positive donor) or nonoccupational exposures (e.g., needlestick injection, piercing, cutting with a sharp object).

Although there is evidence that PEP can decrease the risk of HIV transmission following occupational exposures to the virus (see Guidelines for use of Antiretroviral Agents: Antiretrovirals for Postexposure Prophylaxis following Occupational Exposure to HIV), it is not clear whether these results can be extrapolated to nonoccupational exposures and the CDC states that recommendations concerning the appropriateness of antiretroviral prophylaxis in nonoccupational exposures cannot be made based on currently available information.

A decision to offer such prophylaxis should be individualized taking into account the likelihood of HIV transmission occurring, the potential benefits and risks of such prophylaxis, and the interval between the exposure and initiation of therapy. All individuals evaluated for possible nonoccupational HIV exposure should be counseled to initiate, resume, or improve risk-reduction behaviors to avoid future exposure and prevent possible secondary transmission of HIV.

To facilitate accumulation of information regarding utilization, safety, and efficacy of antiretroviral prophylaxis following sexual or other nonoccupational exposures to HIV, the CDC has established the National Nonoccupational HIV Postexposure Prophylaxis Registry.

Sexual Assault

HIV-antibody seroconversion has been reported among individuals whose only known risk factor was sexual assault or sexual abuse. The overall probability of HIV transmission occurring following a sexual assault depends on several factors, including type of sexual intercourse (i.e., oral, vaginal, anal); presence of trauma in these areas; site of exposure to ejaculate; viral load in the ejaculate; and presence of a sexually transmitted disease as a cofactor. The risk for HIV transmission per episode of unprotected, receptive penile-anal sexual exposure is estimated to be 0.1-3% and the risk per episode of unprotected, receptive vaginal exposure is estimated to be 0.1-0.2%; the risk per episode of receptive oral exposure is unclear but instances of transmission have been reported.

Although there is evidence that PEP can decrease the risk of HIV transmission following occupational exposures to the virus, it is not clear whether these results can be extrapolated to sexual exposures, including sexual assault. The CDC states that recommendations concerning the appropriateness of antiretroviral prophylaxis in sexual assault victims cannot be made based on currently available information and that a decision to offer such prophylaxis to a sexual assault victim should be individualized taking into account the likelihood of HIV transmission occurring (based on the nature of the assault and any high-risk behaviors exhibited by the sexual assailant such as needle-sharing IV drug abuse), the potential benefits and risks of such prophylaxis, and the interval between the exposure and initiation of therapy. Other clinicians suggest that prophylaxis with antiretroviral agents should be part of a comprehensive rape treatment program and should be offered as part of an ongoing counseling process. If a decision is made to use prophylaxis in a sexual assault victim, the 4-week regimen recommended for PEP following occupational exposures to HIV should be used and such prophylaxis should be started within 72 hours of the assault. Because sexual assault victims are at risk for other sexually transmitted disease, including trichomoniasis, genital chlamydial infection, gonorrhea, bacterial vaginosis, and hepatitis B infection, routine empiric anti-infective prophylaxis against these infections and postexposure hepatitis B vaccination is recommended

Antiretroviral agents have been used for PEP in children and adolescents at risk for HIV because of needlestick injuries or sexual assault; however, data are limited to date. Some clinicians suggest that prophylaxis of HIV should be offered as part of treatment programs for pediatric sexual assault victims; however, consultation with a pediatric HIV specialist may be indicated to help select the most appropriate regimen. A retrospective review of children and adolescents offered PEP after needlestick injury (4 patients) or sexual assault (6 patients) revealed that a regimen of zidovudine, lamivudine, and indinavir or zidovudine, lamivudine, and nelfinavir was started in 8 of these patients, but only 2 completed the full 4-week regimen; reasons for noncompliance were financial concerns, adverse effects, degree of parental involvement, and additional psychiatric and substance abuse issues. Only 5 children were available for follow-up and these were HIV negative at 4-28 weeks.

Nonsexual, Nonoccupational Exposures

Nonsexual, nonoccupational exposures that are associated with a risk for transmission of HIV include procedures that involve percutaneous penetration (e.g., needlestick injection, piercing, cutting with a sharp object); contact with mucous membranes; or contact with skin (especially when the involved skin is chapped, abraded, or affected by dermatitis or the contact is prolonged or the involved area extensive).

The risk for HIV transmission per episode of IV needle or syringe exposure is estimated to be 0.67% and the risk per episode of percutaneous exposures (e.g., needlestick) is estimated to be 0.4%. While clinicians may be asked to provide antiretrovirals for PEP in IV drug abusers or other individuals at risk for HIV transmission following nonoccupational exposures to the virus, the CDC states that data are insufficient to date to make a recommendation for or against PEP in these situations.

Clinicians considering use of PEP following nonoccupational exposures should consider that any benefits of such prophylaxis likely will be restricted to situations in which the risk for HIV transmission is high, when prophylaxis can be initiated promptly, and when compliance with the regimen can be ensured. PEP should not be administered routinely or solely at the request of a patient, should not be used following exposures that have a low risk for transmission of the virus (e.g., potentially infected body fluid on intact skin), and should not be used when the individual seeks prophylaxis more than 72 hours after the exposure.